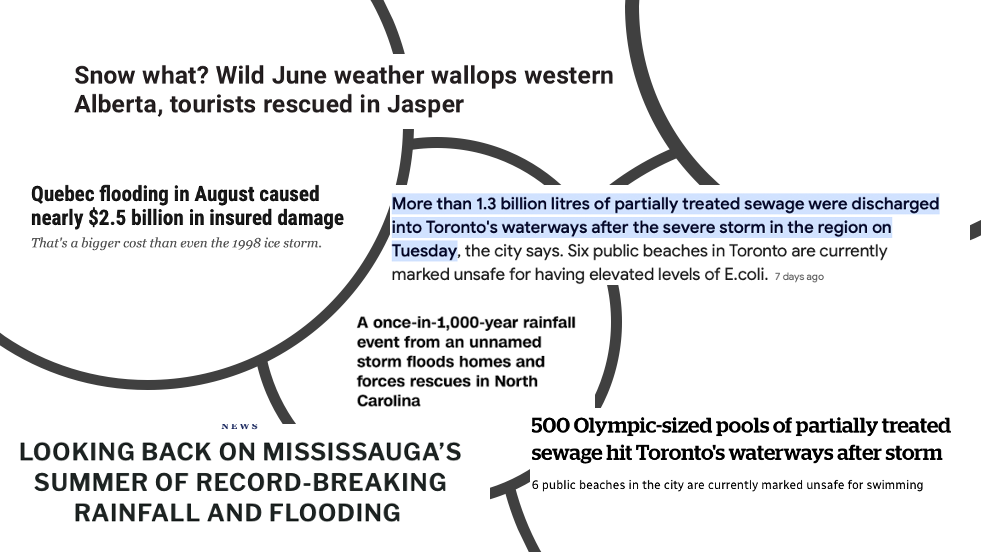

Stormwater. We are breaking the wrong kinds of records

In recent years, weather related headlines could easily be mistaken for the stuff of movie trailers. Those clever hooks used to reel you in, but metrological tracking shows this isn’t fiction created in writers’ rooms. According to Environment and Climate Change Canada, Toronto typically gets an annual average of 831 millimeters, about 32 inches of stormwater. This year, almost half fell in July and August. The July 16th storm in Toronto and surrounding areas accumulated 215.4 mm in roughly three and a half hours, that’s more than a quarter of annual precipitation. Mississauga experienced a trifecta of rainfall, three days that amassed over 270 mm. We are on track to witness our wettest year on record.

Our cities are disrupted. We navigate public transit stations as we wade in water, experience power outages, and endure major highway shutdowns as people’s cars submerge in water like submarines. City service lines, emergency responders and insurance companies are increasingly overwhelmed and overstretched with calls from frustrated residents.

The cost of clean-up and repair parallels big budget film making too.

Headline sources online: Global News, Montreal Gazette, CBC, The Medium, Apple Valley News Now

The perfect storm needs better stormwater management

Populations are more concentrated. More people are using the same infrastructure and drawing from the same water sources. With city space at a premium, urban centres expand up. Building with grey materials like concrete and asphalt increase stormwater runoff or overflow, as they shed water, not soak it up.

Low Impact Development (LID) is a way to better manage stormwater and reduce negative environmental passages. One of the principles of LID is to recreate natural processes to absorb, and clean rain where it falls. Historically, stormwater management channels precipitation through tunnels or small pipelines and treatment facilities. In Toronto these drains are above and below the surface, and primarily at street level. In parts of the city, sewer and stormwater systems co-exist. Combined Sewer Overflow (CSO) is collected through the same pipe, creating headaches with fast and furious downpours. This can flush out sewage and stormwater directly into bodies of water without being treated.

We can intentionally connect living and built environments that better absorb rainwater and support drainage. How? It starts with design. Early collaboration with environmental experts, governing bodies, engineers and landscape architects is a first step. This collective can best assess development sites, soil layers and composition, drainage and weather patterns to steer us towards effective design solutions.

When we retrofit existing roofs, install green roofs on new construction, and expand landscaping we are better equipped to handle severe storms. Mimicking nature is the response as vegetation filters and absorbs stormwater, limiting the amount of water that hits the ground.

Grey infrastructure holds pollutants

Pollutants are widespread. Oils and chemicals from manufacturing, microplastics in tires that wear down and never decompose, animal waste and trash create a toxic cocktail. With urban runoff they contaminate our waterways. When we eliminate our greenbelts for development, we also eliminate natural absorption. With grey surfaces runoff quickly passes through municipal storm drainage systems and directly deposits into our lakes, rivers and streams. With weather patterns increasingly aggressive, these bodies of water rise, cause floods, decrease filtration and burden our communities and property owners.

East Bayfront area in Toronto, a large waterfront development planned with parks and natural trails.

Storms can have a silver lining

Fifteen years ago Toronto was the first North American city to implement a green roof bylaw and eco-roof incentive program City of Toronto Green Roof Bylaw. This offsets the combined environmental impact of the concrete jungle and climate change, a forward step to improve stormwater retention and runoff. The city’s 10-year Toronto Water Budget has allocated $4.3 billion for stormwater management designed to expediate our resilience and mitigate flood risks through strategic measures.

The intent is to raise public awareness while advocating and delivering sustainable practices. Green infrastructure is linked to better absorption and can be achieved by building green roofs, vegetative covered carports and other rooftop oasis’, adding permeable pavements and creating shallow rain gardens to temporarily contain rainfall and snow melts. Integrating natural elements into our construction also benefits the urban heat island effect (UHI) as green spaces are cooling due to evapotranspiration.

Concrete Monkey

The city is reducing the burden on existing stormwater management facilities by upgrading antiquated facilities and building new ones. New systems lean into a more natural approach with preserved and constructed wetlands to filter pollutants, store excess and encourage biodiversity. They also have a broader reach as they are integrated in and around public spaces promoting engagement with nature.

The Toronto and Region Conservation Authority (TRCA) Flood Risk Management works with municipalities and other partners to monitor the performance of stormwater management infrastructure in existing and new developments. Their science-based approach uses data to develop tools, best practices and policies with one goal in mind: better stormwater management to protect, conserve and restore our natural resources and our communities.

As a property owner you should know if you live in a flood vulnerable neighbourhood and what you can do to protect your home and your family. As part of their mandate the TRCA identifies these areas and encourages you to be informed and stay involved, as extreme weather events are Ontario’s leading cause of public emergencies.

The city operates underground storage basins to capture and slowly release water from stormwater management ponds as part of the end-of-pipe control measure. This last stage is designed to hold and treat it before it runs into local water bodies. These storage tanks are dual purposed as they treat the quantity and the quality of stormwater.

The assessment of tactics is ongoing and adaptive. As weather patterns continue to shift, further policy developments and deployments with all levels of governments is required.

Who pays for weather related damages?

We all do.

The footprint and impacts of flooding and other natural disasters affect our communities, our environment and our wallets. This is part of our climate reality, but overburdened infrastructure sets us back further. As we play catch-up and cities impose solutions to manage the challenges of today and meet future needs, Mother Nature doesn’t wait. It’s increasingly more difficult to keep pace with the frequency and the fervour of floods.

Due to the relentless pressure on urban infrastructure, insurance companies say that water damage is the number one cause for property claims in Canada. This summer response time for emergency crews defied the use of the word emergency, with not enough human or equipment resources to meet the need of the storm crisis. If you made a weather-related claim in recent months your insurance company may have factored in a Catastrophe (CAT) fee as a line item on the contractors’ repair estimate. According to IBC this is not standard practice – surge pricing is discretionary, similar to Uber fares increasing with customer demand, but not taxi fares. The fee covers per diem, overtime, transportation and accommodations for the workforce brought in to manage the overflow. Companies calculate the flat fee differently, but you might be surprised to know that it can be thousands of dollars per claim. According to the Insurance Bureau of Canada (IBC/BAC), four weeks this summer, in four provinces resulted in approximately 228,000 claims. That’s a lot of zeros.

Most municipal governments charge property owners a stormwater management fee as part of their water bill. The revenue generated is for ongoing management and system repairs. Amounts vary but are relatively nominal for the investment required to build better infrastructure.

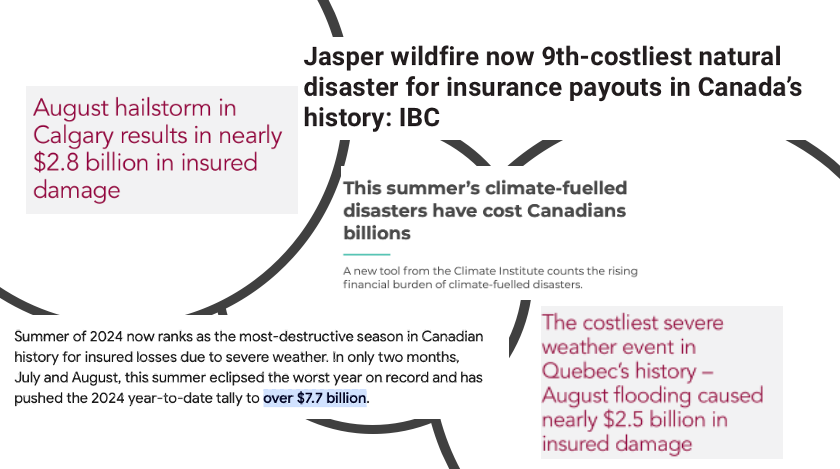

Headline sources online: Global News, IBC, Climate Institute of Canada

Going with the flow

Canada has a Climate Resilience Strategy to adapt to the shifts that are increasingly present in our day to day. It recognizes that flooding repair costs, specifically

in urban centres are expected to increase by 500% in the next 30 years.

This might be a conservative estimate as the IBC/BAC reports that the July storm in Toronto and Southern Ontario brought Sticker Shock damages of almost $1 billion, this before the back-to-back flash floods in Mississauga. The Quebec flood tally is $2.5 billion, and the August hailstorm in Calgary $2.8 billion. The real shock might be that flood coverage is not automatically included in your insurance policy, so floods and sewer backup often require additional coverage. Some city councils are considering or have passed flood relief grant programs for residents caught in the eye of the storms.

Money is a short-term motivator

Tax weary citizens deserve better stormwater management. Savings are possible with education, advocacy and more LID to bring down material and operational costs. Defined maintenance plans that outline aftercare help all of us understand how to avoid costly repairs or replacements for future generations.

This isn’t about dollars and cents. It’s about sense and sustainability. The environmental impact of not managing stormwater is far reaching. It manifests health risks for our water systems, the ecosystems that inhabit them, and the human beings who rely on all of it.

If you like what you’ve read, or have questions, contact Milena at m.smodis@ginkgosustainability.